Lawrence and Colonialism

The question of Lawrence’s relation to colonialism has been a continuous thread during his lifetime and after his death. His involvement with the Arab Revolt of 1916–1918 was strongly motivated by a desire to achieve Arab independence as well as his own ambition, but this intention was fatally undermined from the start by the Sykes-Picot Agreement in which Britain and France had already agreed to divide up and dominate the Middle East between them. Lawrence found he was forced to lie to the leaders of the Revolt who demanded promises that Britain would not betray their cause.

This dualism and/or ambivalence is reflected in Lawrence’s references to colonialism in his writing. Throughout his life, he expressed wildly differing opinions, from ardent support for Arab independence to disgust with debasing himself by living in Arab culture.

After the war, Lawrence was involved in continued negotiations during the Paris Peace Conference and later in the Colonial Office to redraw the Middle East as a series of nations with varying degrees of colonial control/independence, and eventually to establish Arab Revolt leader Emir Faisal as King of Iraq.

Emir Faisal

Emir Faisal (1885–1933), the third son of Sherif Hussein of Mecca, was the leader of the Arab Revolt campaign, but after the capture of Damascus he was forced out by the French authorities who had claimed control of Syria. He later became King Faisal I of Iraq, partly influenced by persuasion from British figures including Lawrence and Gertrude Bell.

Faisal is pictured here entering the temporary French hospital at Akaba along with Nasib and Captain Rosario Pisani, the French North African leader of the Arab Northern Army during the Revolt. A shadow can be perceived of the person taking the photograph at the bottom of the image, which may well be Lawrence himself. The photograph is likely to have been taken sometime around August 1917 when Faisal’s forces assembled following the capture of the port of Akaba from inland. This photograph, hand-labelled by Lawrence, is part of a series owned by David George Hogarth.

Hogarth Papers, P452/MIL/3.

Druses entering Damascus

The city of Damascus was captured on 30th September 1918 by Arab forces, followed by British and Australian forces, marking the culmination of the Arab Revolt and the overthrow of Ottoman control in Syria. This photograph shows members of the Druse tribe, who fought as part of Emir Faisal’s Arab forces during the Revolt, entering the city on horseback. Driving the other way are British officers in an open top car; the British would shortly hand over control of Syria to French authorities under the terms of the Sykes-Picot Agreement despite their promises of creating an independent Arab state.

Lawrence labelled the photograph “In Damascus: Druses entering”.

Hogarth Papers, P452/MIL/3

Burned in Effigy

Lawrence was intensely curious about the public’s views of his exploits. This is his own clipping from a newspaper scrapbook he kept in colonial India (now Pakistan), and shows his own picture being burned in London on 21 January 1929 during a protest by Communists against his apparent espionage activities in Afghanistan. Lawrence was in reality returning to the UK on a passenger ship after being stationed in an R.A.F. base near the Afghan border for several months.

Acc. 2021/44

Lawrence on Film

David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia

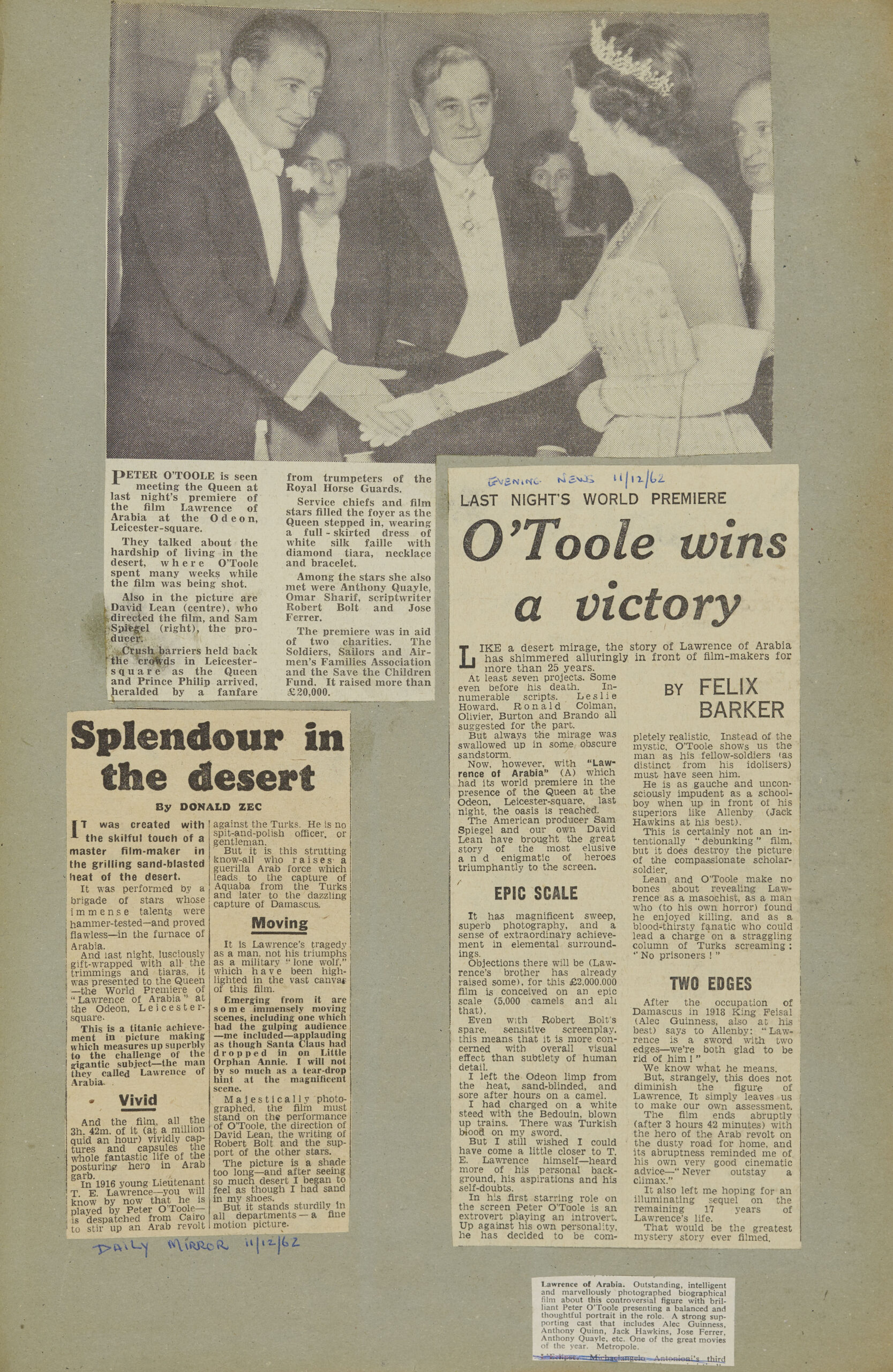

Plans for a film of Lawrence of Arabia began as early as the 1920s, and included Alexander Korda’s project in 1934, which was rejected by Lawrence himself. A film finally came out in December 1962, starring Peter O’Toole, and directed by David Lean with a script written by Robert Bolt. The film attracted controversy at the time because, although judged as a dramatic masterpiece, many felt that it was not an accurate portrayal of Lawrence’s character. The film was also seen by some critics to have a distinct anti-colonialist agenda. Today, many might find the film to be controversial for different reasons due to the portrayal of Middle Eastern characters by white actors.

Letter from George Bernard Shaw to D.G. Hogarth about a potential Lawrence film, 3 June 1927. Bernard Shaw discusses the possibility of Lawrence blocking any film projects on the grounds that his work has been copyrighted or his life has been misrepresented.

Hogarth Papers, P452/REL/2/1

Scrapbook

Scrapbook containing articles and photographs on the film Lawrence of Arabia directed by David Lean.

Wilson Papers, P450/R/ORR/6/3/5

Death

Lawrence died on 19 May 1935 at the age of 46, having been fatally injured in a motorcycle accident near his home at Clouds Hill, Dorset, six days earlier. He had unexpectedly run into two boys on bicycles in a country lane, crashing over his motorbike’s handlebars. Lawrence’s death led to research on brain injuries and was influential in the introduction of helmets for motorcyclists through the work of Sir Hugh Cairns (1896–1952).

The fatal accident has attracted controversy over the years, with many believing the death to be a political conspiracy carried out by a mysterious “black car” spotted driving along the road.

On the fatal day, Lawrence was going to the Post Office to send a telegram to the writer Henry Williamson (1895–1977) about arrangements to meet. Williamson later claimed that this related to a discussion over introducing Lawrence to Hitler. This was seen by Jeremy Wilson to be the product of retrospective imagination.

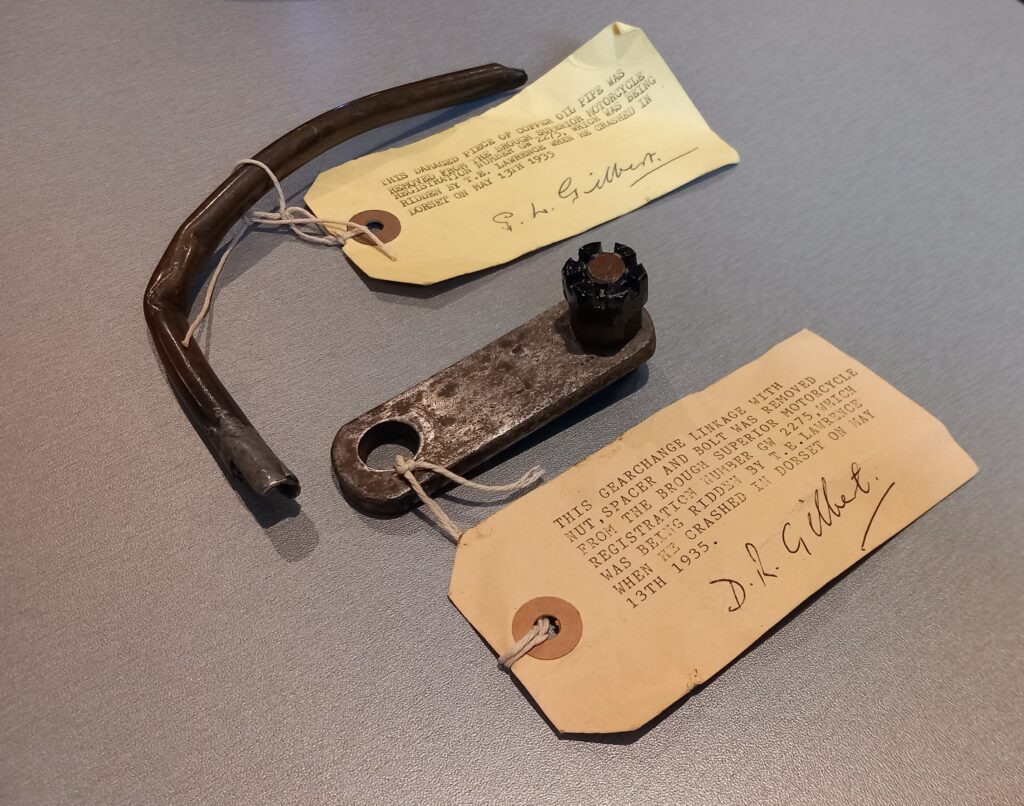

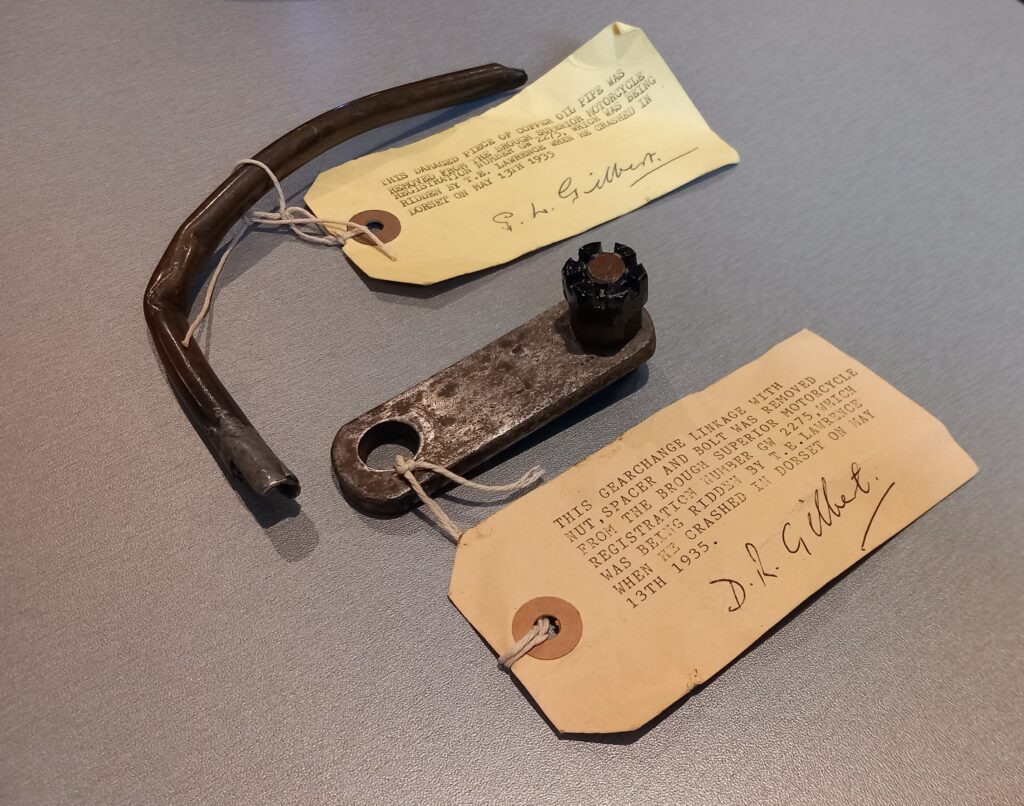

Parts belonging to Lawrence’s final motorcycle

Copper pipe and front fork from T.E. Lawrence’s Brough Superior GW 2275, the motorcycle on which he crashed on 13 May 1935.

A Brough expert has cast doubt on the authenticity of the front brake part, suggesting that it could not have belonged to the motorcycle at the time of Lawrence’s crash, although the previous owner’s labels attest to the authenticity of the pieces as part of GW 2275.

Acc. 2021/93. Loan from the T.E. Lawrence Society

Newspaper reports

Newspaper reports on Lawrence’s death, inquest and funeral including theories on the “black car.”

Wilson Papers, P450/R/ORR/6/1

Postcard from Henry Williamson c. late 1960s

Henry Williamson writes to A.W. Lawrence that he will allow his claims about the “proposed meeting with A.H” [Adolf Hitler] to “fade away”. He also discusses the John Bruce scandal and on the reverse, discusses the futility of his “Hitler peace dream”.

Wilson Papers, P450/R/COR/4/16

Utterly Ignorant

In 1968, Henry Williamson still maintained that a letter proposing a meeting with Adolf Hitler had been lost during Lawrence’s accident, although an actual letter to Lawrence survives which merely proposes a visit by Williamson to Clouds Hill. Jeremy Wilson’s long-term research assistant Dr Lilith Friedman, who had escaped anti-Jewish persecution in Austria in 1938, wrote this letter to The Times denying Lawrence’s interest in Nazism.

Wilson Papers, P450/R/ORR/6/2